Between the Lakes Treaty (No. 3)

What land does the treaty cover?

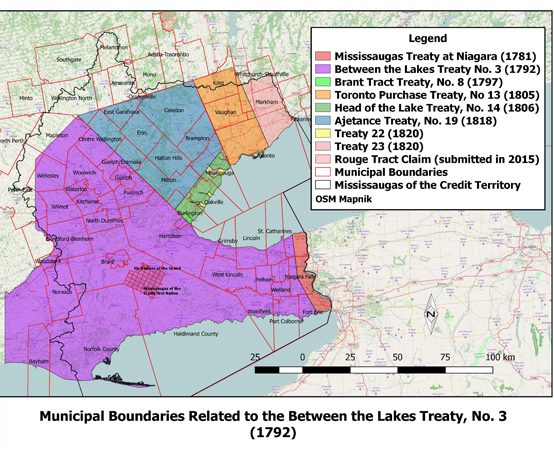

The Between the Lakes Treaty (No. 3) was negotiated in 1784 and updated in 1792. The Treaty, between the Mississaugas of the Credit and the British Crown, covers approximately 3 million acres between lakes Erie, Huron and Ontario. The present-day City of Hamilton is covered by this treaty. You can read the full text in this exhibition (scroll down).

Today, multiple urban centres exist on the Between the Lakes Treaty territory, including Hamilton, Waterloo, St. Catharines and Guelph. The present-day reserves for both the Mississauga of the Credit and Six Nations exist within the original Haldimand Tract.

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/hamcivmus/public_html/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/hamcivmus/public_html/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

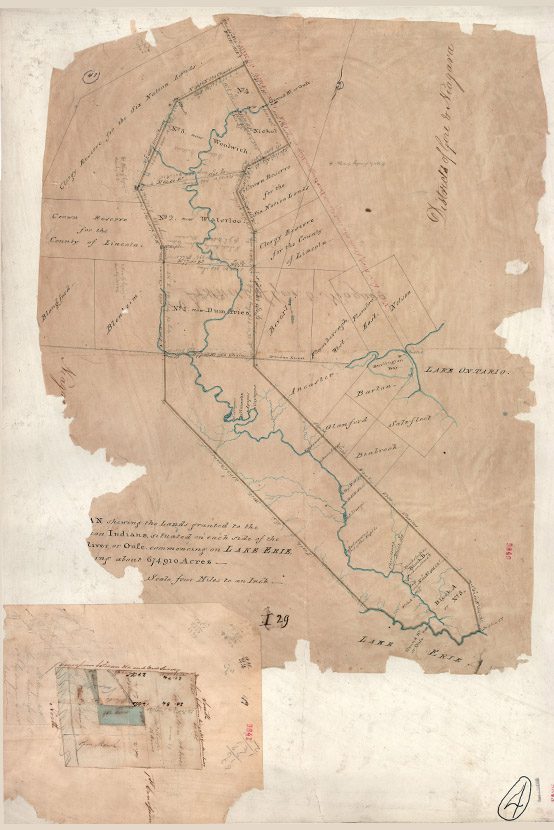

The text outlines details of the 1784 Treaty, including the lands covered in the agreement. According to the document, for £1180 worth of trade goods, the Mississauga ceded

“all that tract or parcel of land lying and being between the Lakes Ontario and Erie, beginning at Lake Ontario four miles south westerly from the point opposite to Niagara fort, known by the name of Messisague Point, and running from thence along the said lake to the creek that flows from a small lake into the said Lake Ontario known by the name of Washquarter; from thence a north westerly course until it strikes the River La Tranche or New River; thence down the stream of the said river to the part or place where a due south course will lead to the mouth of Cat Fish Creek emptying into Lake Erie, and from the above mentioned part or place of the aforesaid River La Tranche following the south course to the mouth of the said Cat Fish Creek; thence down Lake Erie to the lands heretofore purchased from the Nation of Messissague Indians; and from thence along the said purchase to Lake Ontario at the place of beginning as above mentioned, together with the woods, ways, paths, waters, watercourses, and appurtenances to the said tract or parcel of land belonging.” (extract from the Treaty text)

According to the Haldimand Proclamation of 25 October 1784, 550,000 acres (out of the 3 million total) were granted to Haudenosaunee who were loyal to the crown. The original tract consisted of 6 miles on both sides of the Grand River, from its mouth to source, although this territory has shrunk substantially since this time (owing to long-term leases, sales, Crown negotiations). The Haldimand Proclamation stated

“Whereas His Majesty having been pleased to direct that in consideration of the early attachment to his cause manifested by the Mohawk Indians and of the loss of their settlement which they thereby sustained - that a convenient tract of land under his protection should be chosen as a safe and comfortable retreat for them and others of the Six Nations, who have either lost their settlements within the Territory of the American States, or wish to retire from them to the British - I have at the earnest desire of many of these His Majesty's faithful Allies purchased a tract of land from the Indians situated between the Lakes Ontario, Erie and Huron, and I do hereby in His Majesty's name authorize and permit the said Mohawk Nation and such others of the Six Nation Indians as wish to settle in that quarter to take possession of and settle upon the Banks of the River commonly called Ouse or Grand River, running into Lake Erie, allotting to them for that purpose six miles deep from each side of the river beginning at Lake Erie and extending in that proportion to the head of the said river, which them and their posterity are to enjoy for ever.” (extract from the Proclamation text)

Why was the

treaty negotiated?

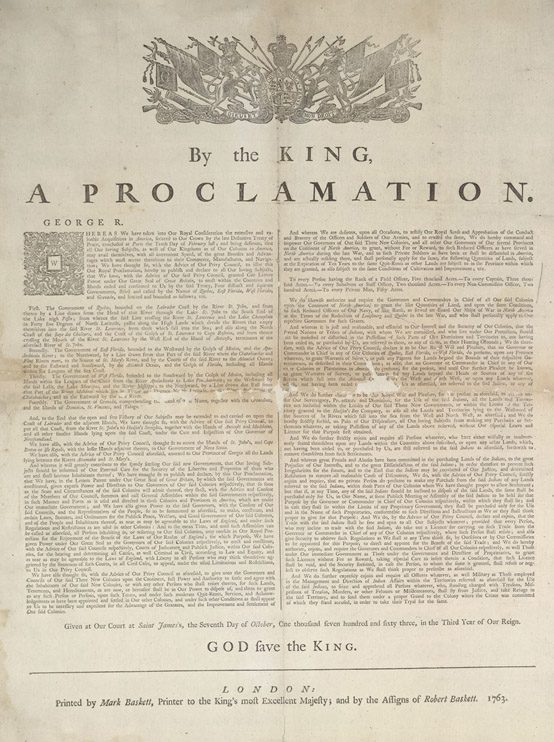

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 recognized Indigenous sovereignty over the land they occupied and required that if the Crown needed land for military or settlement purposes, they had to purchase it from the Indigenous occupants.

Therefore, when the Crown required land on which to settle Loyalists forced from their homes in the United States, following the American Revolution (1765-1791), they had to negotiate with the Mississaugas, through Col. John Butler. At the time the treaty was made, the Mississauga,

“occupied, controlled, exercised stewardship over approximately 3.9 million acres of land, water in resources in Southern Ontario…with their lands extending from the Rouge River Valley westward to the headwaters of the Thames River, down to Long Point on Lake Erie, following the shoreline of Lake Erie, the Niagara River and Lake Ontario, until arriving back at the Rouge River Valley.” (source: MNCFN.ca)

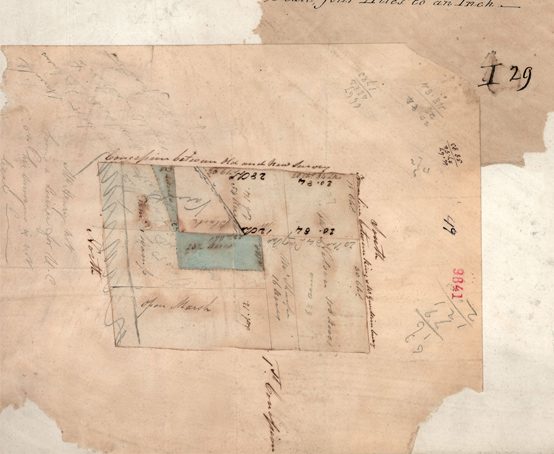

Library and Archives Canada

Library and Archives Canada, 2000215462

What were the terms of the treaty?

The Between the Lakes Treaty is not a long document and focuses largely on defining the boundaries of the land ceded to the Crown. Despite their brevity, treaties are complex documents, which require historical and cultural context to be best understood.

When it comes to comprehending treaties between the Crown and Indigenous people, what is said is just as notable as what isn’t addressed. For example, treaties do not discuss stewardship of the land, self-determination, the right to be sustained by their land (to hunt, fish and gather), or water rights, all of which are key considerations for the Mississauga of the Credit and other Indigenous people.

Written in English and in the colonial, settler tradition, the outright ownership of land that this and other treaties detail was a foreign concept to Indigenous people, whose world view did not commodify land and resources as Europeans did.

Further, in a number of cases, the treaty text differs from contemporaneous Indigenous oral histories and wampum belts, with the written treaties favouring Crown interests at the expense of Indigenous communities. This, in addition to bad faith negotiations, treaty responsibilities not being honoured or unclear title and transfer of land in question, has led a number of Indigenous communities in recent years to submit land claims, requesting that the government right historical wrongs. One such modern land claim is the Rouge Tract Claim, submitted to the government by the Mississaugas of the Credit in 2006.

Between the Lakes Purchase and Collins Purchase, No. 3

J. GRAVES SIMCOE

THIS INDENTURE made at Navy Hall in the County of Lincoln, in the Province of Upper Canada on the seventh day of December in the year of Our Lord one thousand and seven hundred and ninety-two, between Wabakanyne, Wabanip, Kautabus, Wabaninshop and Nattoton, on the one part, and Our Sovereign Lord George the Third, by Grace of God of Great Britain, France and Ireland, King of Defender of the Faith, &c., &c., on the other part.

Whereas, by a certain indenture hearing date the twenty-second day of May, in the year Our Lord one thousand seven hundred and eighty-four, and made between Wavakanyne, Nannibosure, Pokquawr, Nanaughkawestrawr, Peapamaw, Tabendau, Sawainchik, Peasanish, Wapamanischigun, Wapeanojhqua, Sachems and War Chiefs and Principal Women of the Messisague Indian Nation on the one part, and Our said Sovereign Lord George the Third, King of Great Britain, France and Ireland, &c., &c., the other part.

Your Questions, Answered

Do you have burning questions that may even feel a bit uncomfortable to ask out loud? This is a space for open, honest and truthful exchanges when talking about treaties.

The Between the Lakes Treaty (and others) remain relevant today as the Crown and Mississauga committed to a relationship with each other during the original treaty negotiations. Despite the Crown’s commitment to relationship, which is enshrined in treaties, colonial agents have often tried to downplay the sacred nature of treaties to pursue state goals. The Crown has continually tried to reduce the treaties to mere real-estate deals. The legalistic language found in the written versions of treaty texts, on which the Crown relies, often miss the sacred and binding character of the treaties emphasized during the oral negotiations. For the Crown, the Royal Proclamation of 1763, articulated by King George III, established the constitutional structure for treaty-making in North America. This structure was renewed in section 35 of the Constitution Act (1982) by recognizing and affirming Aboriginal and Treaty rights. In other words, treaties are the foundation of the Canadian state and are still legally binding today.

— Emma Stelter, Governance Coordinator and Policy Analyst, Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation

Settlers continue to have obligations (such as peace, friendship, and respect) under treaties to this day based on the alliances and relationships formed during the original treaty negotiations. The alliance between the Crown and the Anishinaabek was first established in Niagara in the summer of 1764, when over 2,000 Chiefs from 24 nations met with British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Sir William Johnson, to establish peace and form new relationships after the conclusion of the Seven Year’s War. With the British asserting colonial authority in North America, Johnson circulated the Royal Proclamation and presented the Covenant Chain Wampum Belt, 24 Nations Wampum Belt, and 24 Medals. Johnson needed to secure political, military, and commercial alliances with the Anishinaabek and other nations present who were formerly allied to France.

In the treaty negotiations, the old alliances between France and First Nations were symbolized by an iron chain, which was weak and prone to rust. Whereas the new relationship proposed by Johnson between the Crown and First Nations would be symbolized by a silver chain that was too strong to break, but needed to be polished to prevent tarnishing. This polishing is a metaphor for the continual renewal of relationships. First Nations responded to Johnson by presenting the Two Row Wampum Belt, demonstrating their understanding and acceptance of the treaty. All of these together, called the Treaty of Niagara, established a peace and alliance between the First Nations present and the Crown. The Treaty of Niagara is often referred to as the Magna Carta of Indigenous rights as it affirms Indigenous title and ensures colonial non-interference. This treaty remains in place today, and the chain continues to need polishing. The relationships encoded in the Covenant Chain form the basis for the land treaties between the Mississauga and the Crown.

— Emma Stelter, Governance Coordinator and Policy Analyst, Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation

Who are the treaty holders?

The Mississaugas of the Credit relocated to their present location after settler encroachment and inability to gain title to their land holdings at the Credit River necessitated the removal of their village.

The Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation Reserve is situated a thirty-minute drive south of Hamilton along Highway Six near the town of Hagersville. The Reserve consists of approximately 6000 acres of farmland and Carolinian Forest adjoining the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve and straddling Brant and Haldimand Counties.

One-third of the First Nation’s total membership of roughly 2700 band members lives on the reserve with the balance living primarily in the Golden Horseshoe Area of Southern Ontario. The MCFN vision for the future includes a “strong, caring, and connected membership that respects the earth’s gifts and protects the environment for future generations. The vision recognizes its Anishinaabe (Ojibway) roots- our history, language, culture, beliefs, and traditions” which will inform the programs and services offered to the MCFN membership.

The First Nation is led by a council consisting of seven counsellors and a chief elected from its membership every two years. The council meets on a weekly basis to discuss issues of importance to the community. The council does not administer the day-to-day affairs of the First Nation, but such tasks are the responsibilities of its administrative staff. Administrative Departments include Public Works, Governance, Consultation and Accommodation, Lifelong Learning, Social and Health Services, Communications, and Lands, Research and Membership.

Since their arrival in Southern Ontario during the latter part of the 17th century, the Mississaugas of the Credit have been a resilient and dynamic people adapting to the changing geographic, social, political and economic landscape as the times warranted. In their past, the Mississaugas had gained their sustenance from hunting, fishing, and gathering; then they transitioned to an agrarian lifestyle becoming adept farmers. Moving forward into the 20th century,

farming gave way to working in manufacturing jobs in nearby Brantford and the greater Hamilton area. Currently, the First Nation finds itself in a period of transition as it now owns an energy company, and owns the Mississaugas of the Credit Business Corporation which seeks to contribute to the self-sufficiency of the First Nation through the development of projects and partnerships throughout its treaty lands and territory.

The First Nation has always been a proponent of education among its people. Children are educated on reserve at the Lloyd S. King Elementary School and attend high school in nearby Hagersville and Brantford. Anishinaabe culture and language classes are taught to the students at the elementary school while adult learners may partake of language and culture classes offered by the First Nation throughout the course of the year. An annual historical gathering is held in the spring, welcoming all interested parties to explore the history of the Mississauga people; while every August, a traditional powwow and homecoming does the same as a celebration of Mississauga culture and tradition.

- MCFN Official Website

- MCFN Land Acknowledgement Guidelines

- History of the Credit River Missisaugas (PDF, 14.4 MB)

Follow MCFN on social media:

We would like to thank the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation and the invaluable contributions of Darin Wybenga and Caitlin LaForme. The content for the Between the Lakes (No. 3) Treaty was created in partnership with them and it launched in 2021 as part of Hamilton 175, a digital commemoration of the 175th anniversary of Hamilton’s incorporation as a city.