Challenges to Freedom: 1900 to World War II

New Century – Old Attitudes

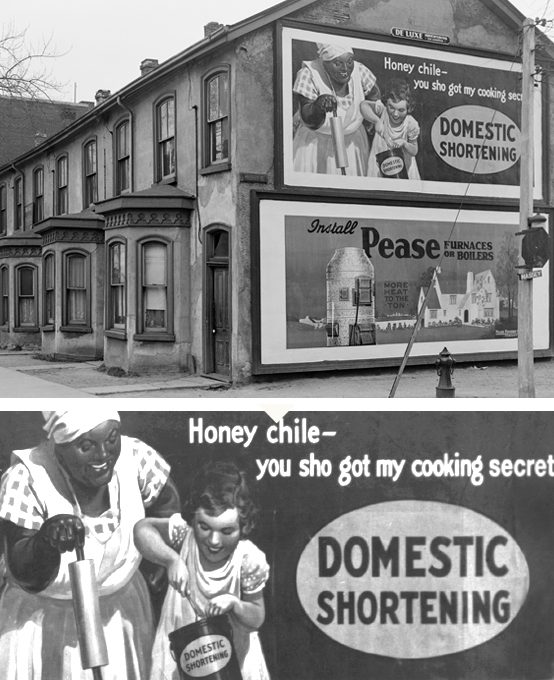

By the turn of the century, African Canadian men and women had earned the rights and privileges of all Canadians to live in equality and dignity. However, events in Canada and around the world would reveal that the position of Black people had reached a new low.

Beginning in the 1880s, Europe colonized and carved up the continent of Africa. African people would remain under direct European rule for the next seventy years. In the same period, the rise of Jim Crow segregation in the American South took away rights and freedoms that African Americans had gained immediately after the Emancipation of the slaves in the United States. The rise of pseudo-scientific theories of race from 1870-1930 placed Africans at the bottom of the human hierarchy.

Canadian society was influenced by this chain of events. Whites did not view Blacks as equals and restricted them from partaking in much of the fruit of citizenship. As a result, Blacks could often not eat in restaurants, stay in hotels, sit on the main floor of theatres, play golf, tennis, or skate at local rinks—the gamut of activities other Canadians enjoyed. Many areas had restrictive covenants whereby African Canadians could not own or rent property and some towns had “sundown laws” that ordered them out before nightfall.”

Last Hired First Fired

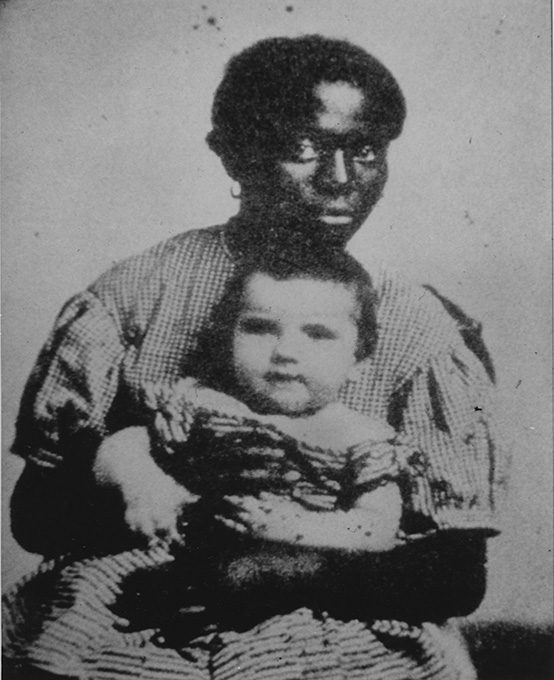

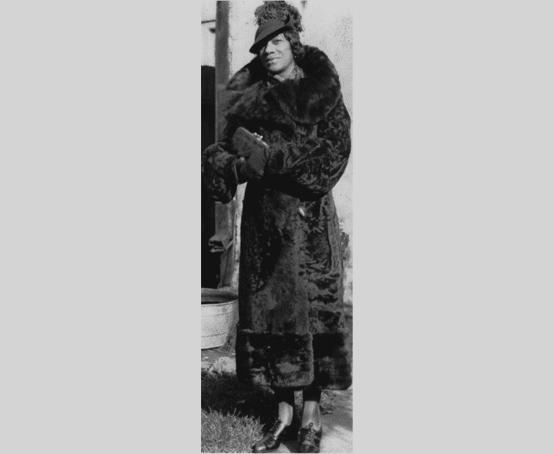

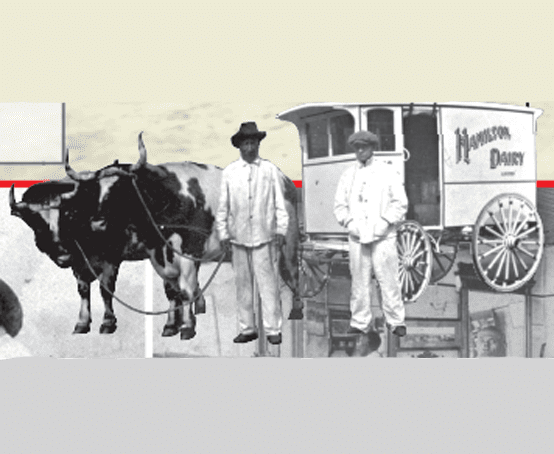

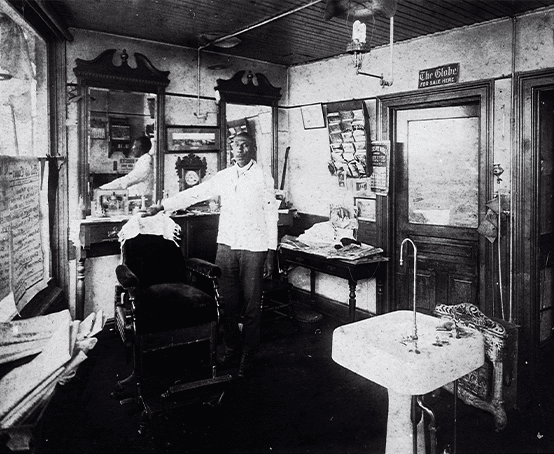

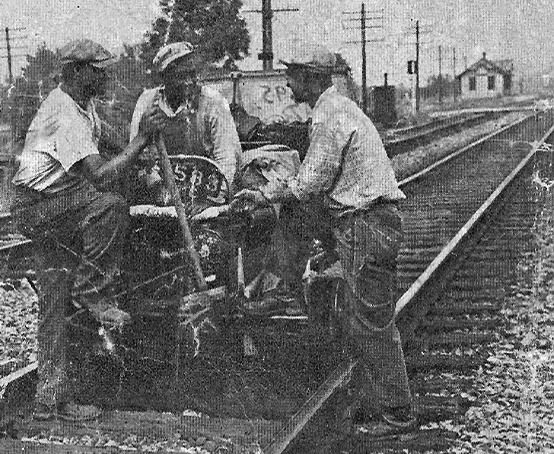

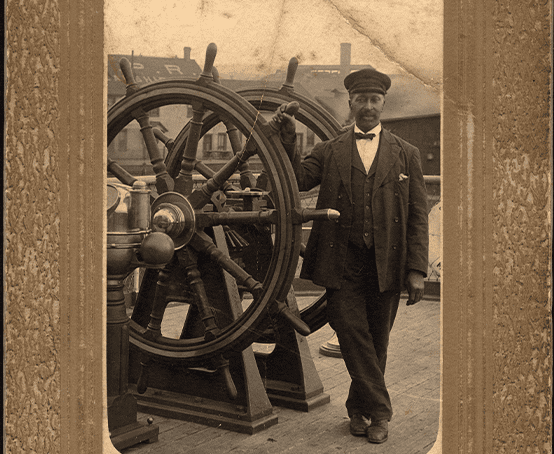

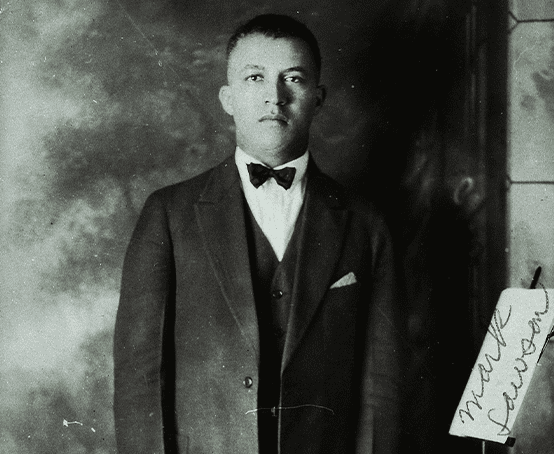

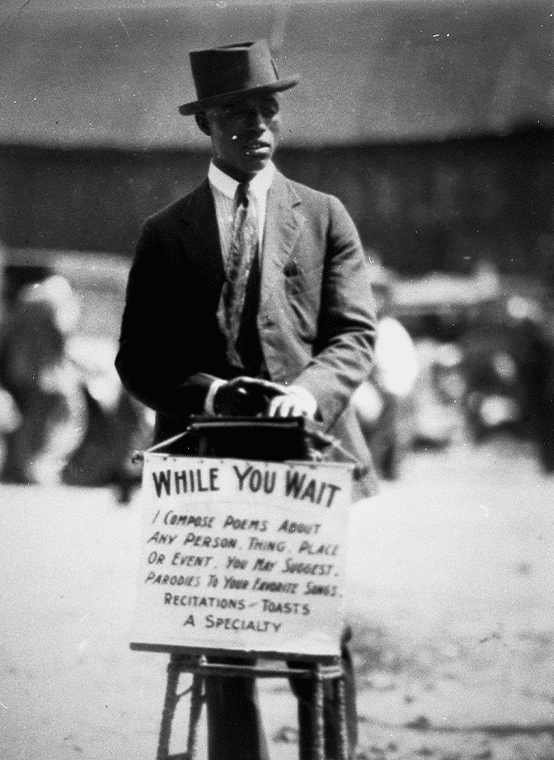

Black workers were excluded from the emerging union movement and tended to be restricted to the lowest status, lowest pay and most servile jobs. The situation of Black workers could be summed up in the old adage: ‘last hired, first fired.’

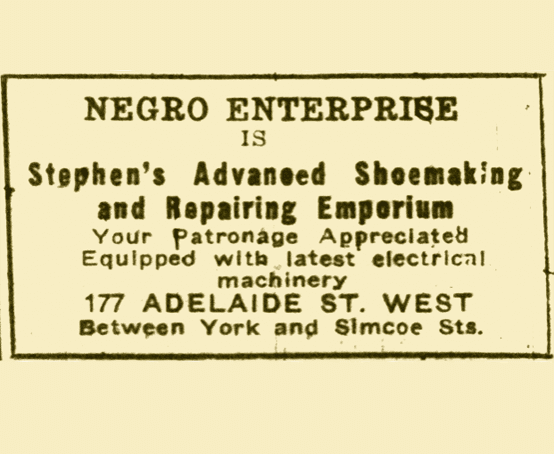

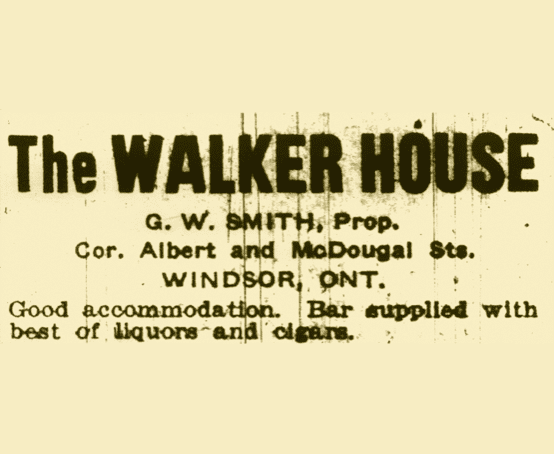

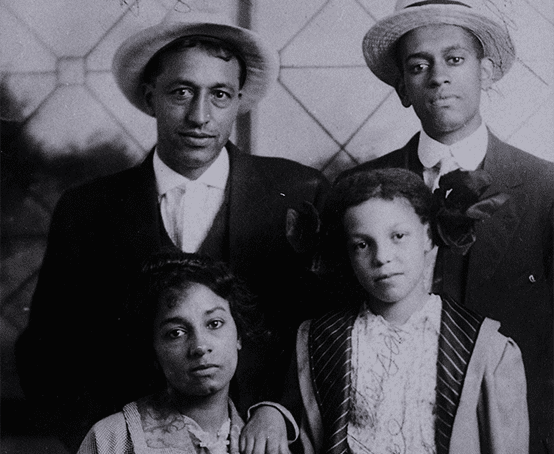

Despite the odds, Black men and women contributed in a variety of occupations.

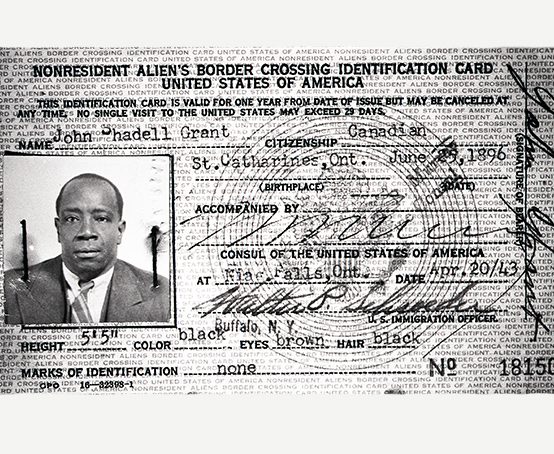

Exodus

Racist immigration policies ensured that no more than a few Black people trickled into the county. The Canadian government moved to restrict African settlement in Alberta and the Prairies and it went out of its way to discourage employers from bringing in Caribbean workers in eastern and central Canada.

However, the bigger untold story was the flood of migration out of Canada by many young and not so young Blacks to the United States. Aspiring nurses, doctors, and other professionals trained at segregated Black colleges in the United States. Most did not return.

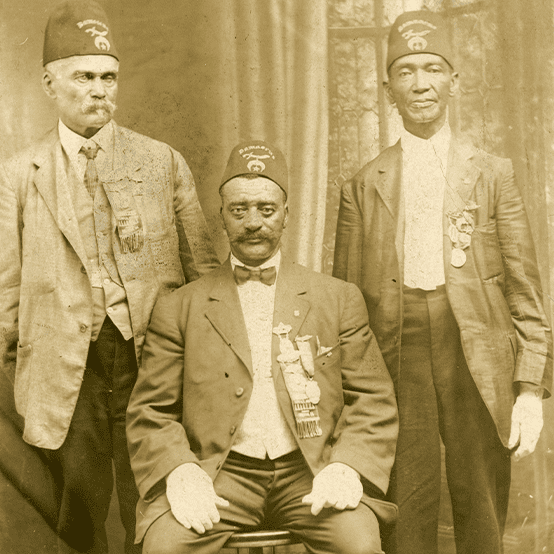

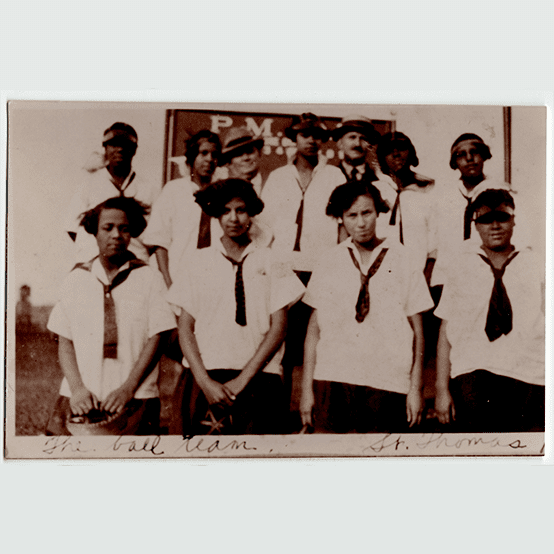

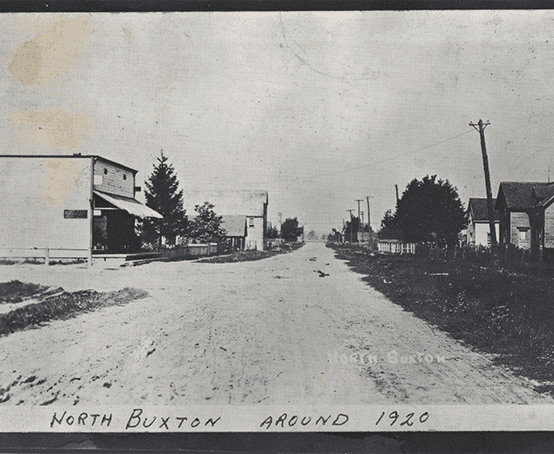

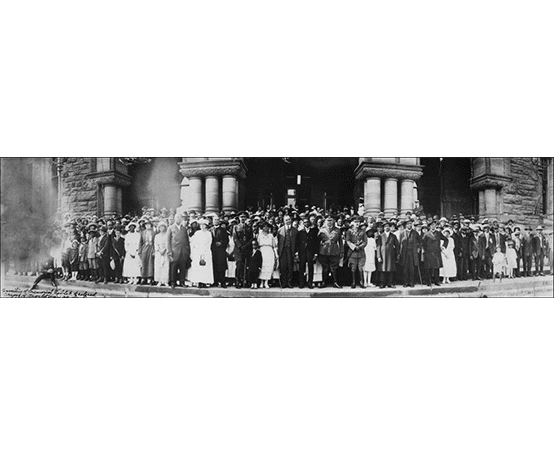

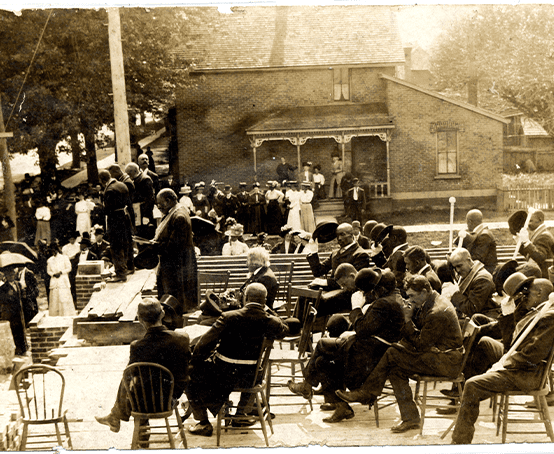

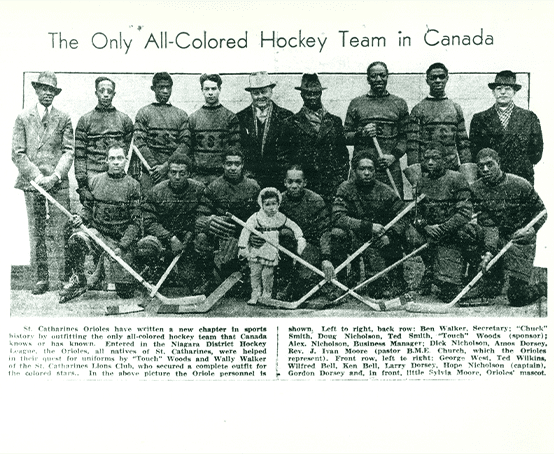

A Separate World

Excluded from the mainstream, African Canadians found solace in their segregated communities, churches, clubs and schools. Run largely by unpaid volunteers , these institutions provided a needed break from racism and the daily grind.

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/hamcivmus/public_html/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/hamcivmus/public_html/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

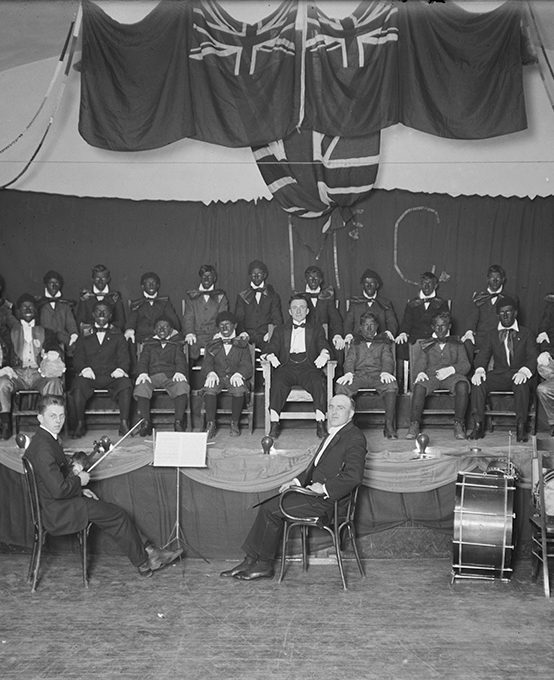

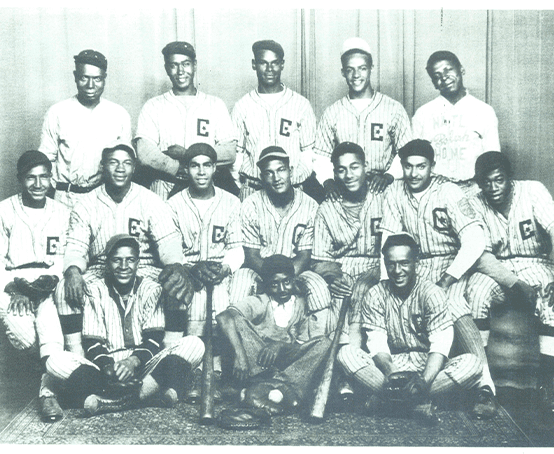

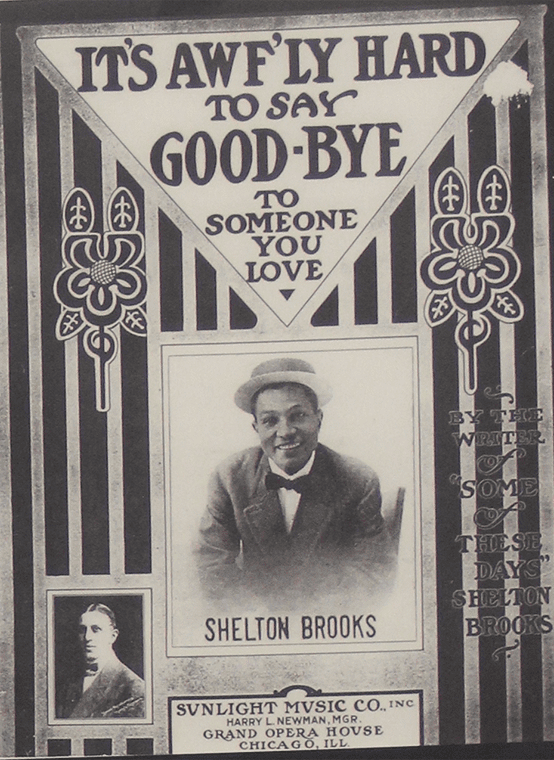

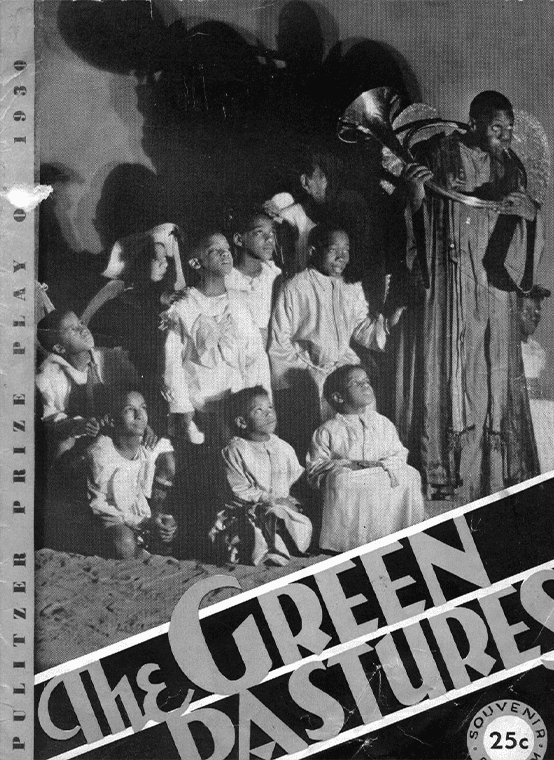

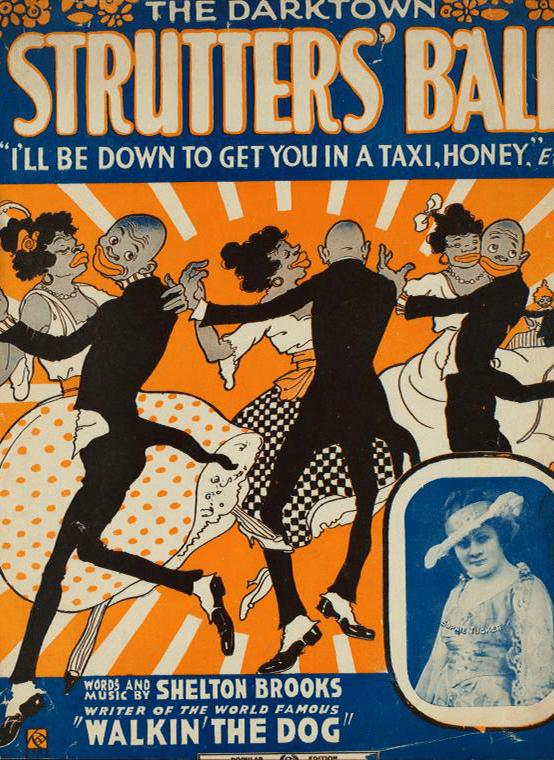

They Made a Joyful Noise...

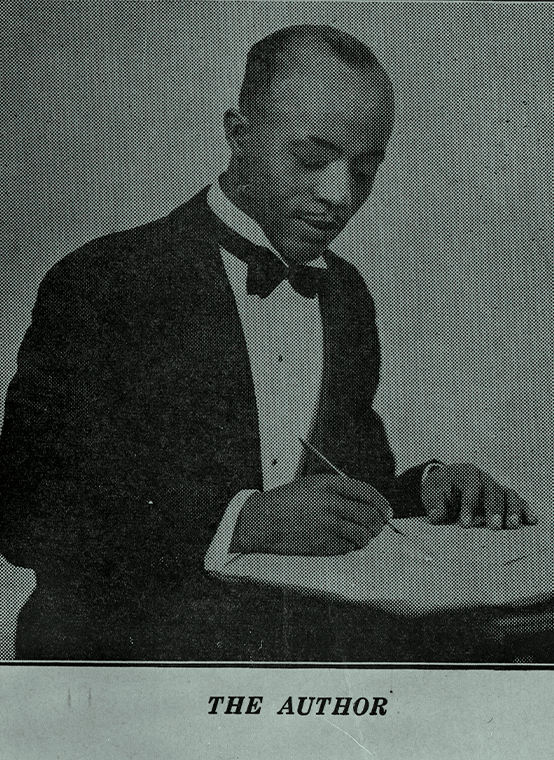

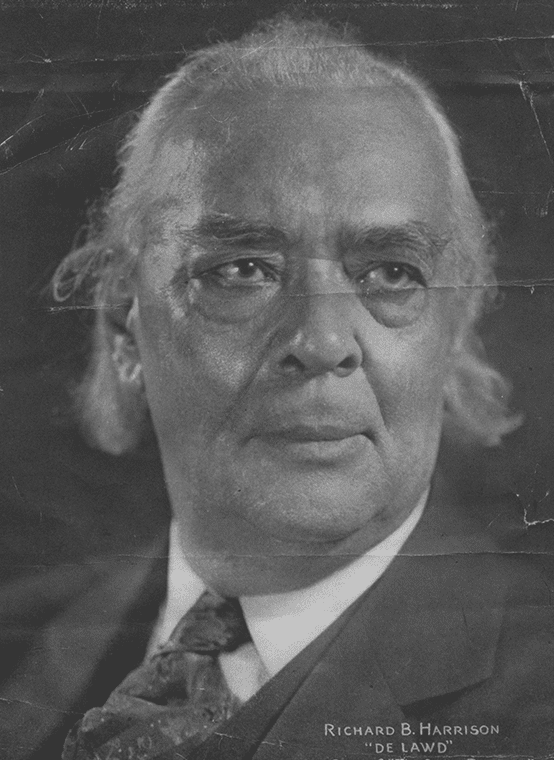

As in the United States, African Canadians often gained more acceptance as “entertainers” than they did in the everyday work world. Those with special talents made their mark as musicians, composers, actors, writers and sports figures. Many opted for the “big time” south of the border.

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/hamcivmus/public_html/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/hamcivmus/public_html/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2