Demanding Our Rights: WWII to 1960s

WWII – A Turning Point

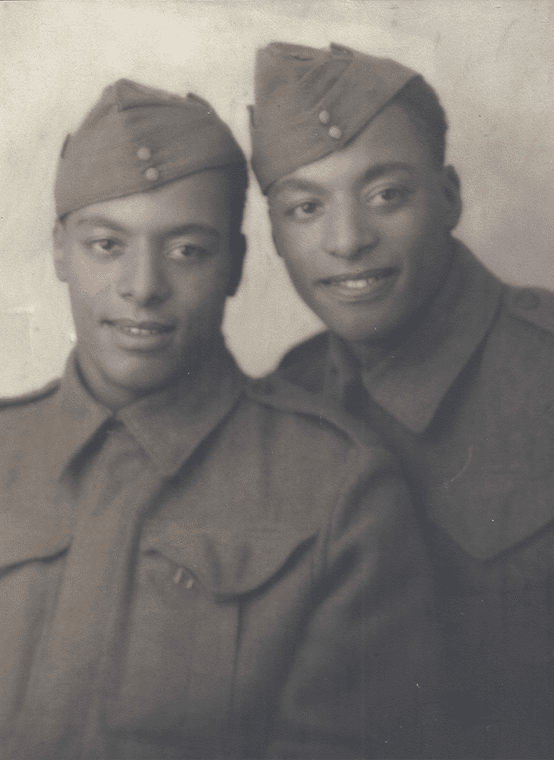

When Canada entered World War II, officials again moved to bar Black men from any involvement. The latter protested and eventually secured the right to enlist. This time they were not segregated into a special construction unit, but were allowed to fight alongside white soldiers.

Men from Jamaica and other Caribbean countries also enlisted in the Canadian armed forces. After the war, these soldiers were able to apply for landed immigrant status.

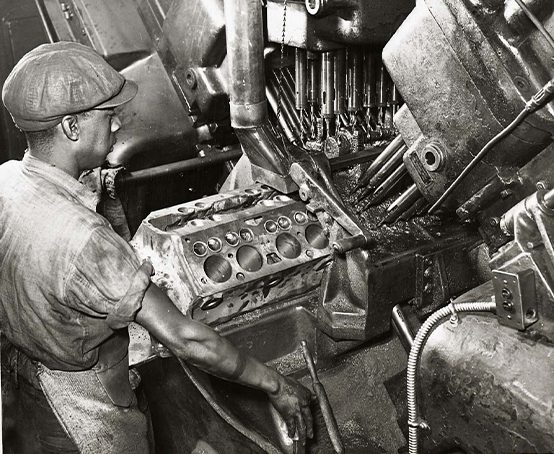

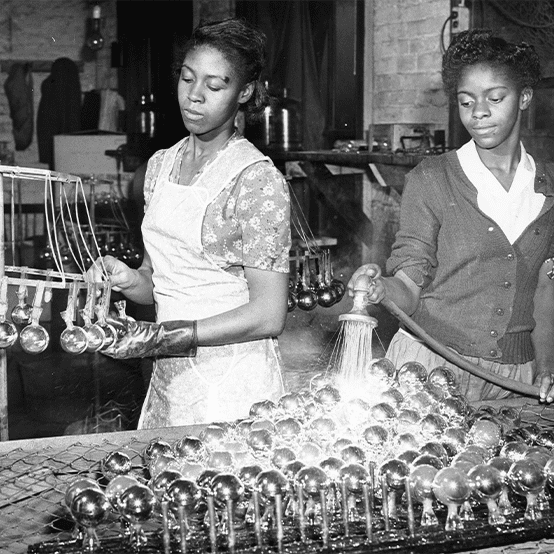

Ironically, it was Canada’s entry into WWII that first opened the doors of opportunity – if only just a crack – for Canadian women and racialized minorities. Black Canadians, who had been shut out of industry after industry for decades, began to take the positions left behind by servicemen who fought overseas.

A Crack in the Door of Opportunity

The Ford plant in Windsor hired its first full-time employees of African descent in the 1940s. Black women worked alongside white women in factories and munitions plants across the country. It was a hopeful beginning.

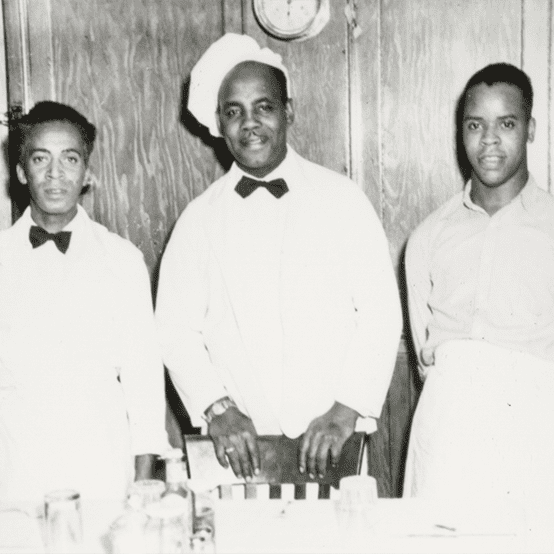

Many other Black workers remained in the same types of jobs they had always held.

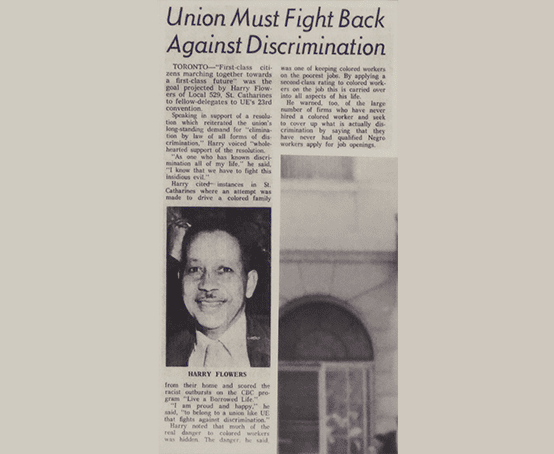

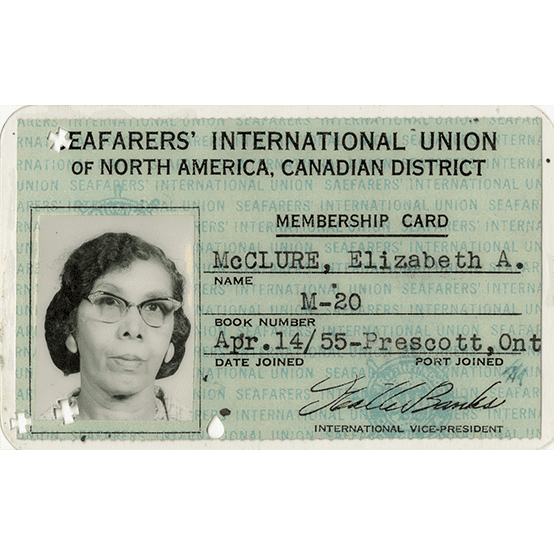

Black Canadians and Labour Unions

For the first time, African Canadians became involved in labour unions, fighting for better wages and working conditions.

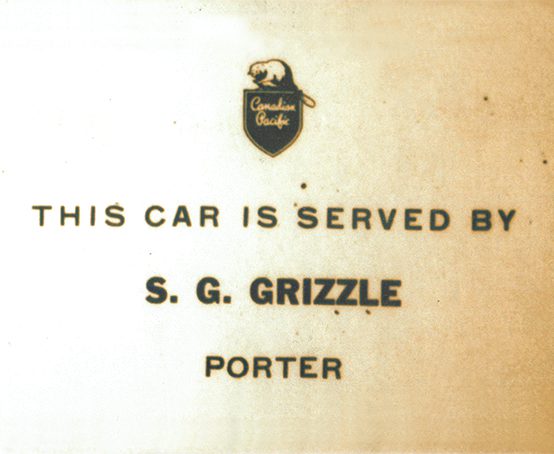

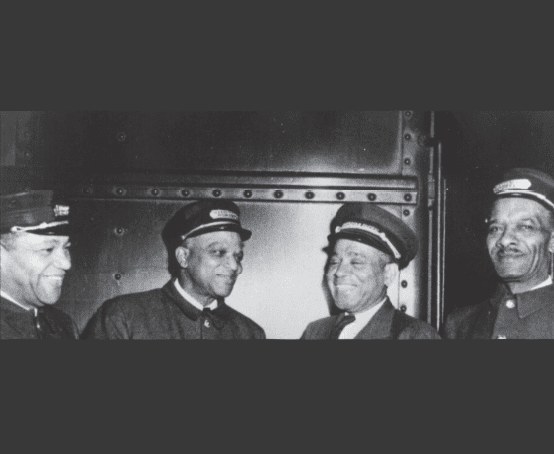

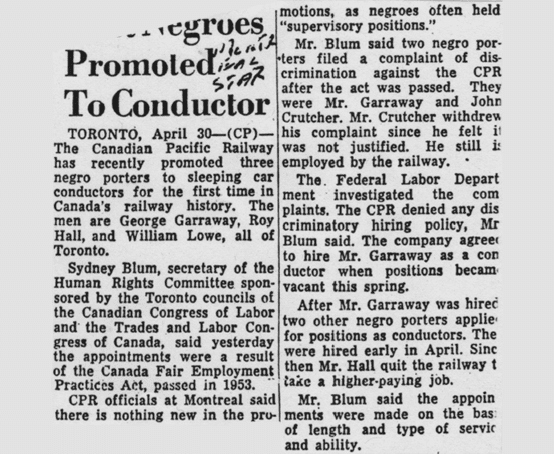

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was an all-Black union that is one of the great success stories in Canadian Black history. In 1942, under the brilliant tutelage of African American labour leader A. Philip Randolph, it established divisions in Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg (and later Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver), and on May 18, 1945 it signed its first collective agreement with CP Rail. With this agreement, porters’ wages and time off were increased and their total hours on the job were reduced. This marked the first time that a trade union organized by and for Black men signed an agreement with a Canadian company.

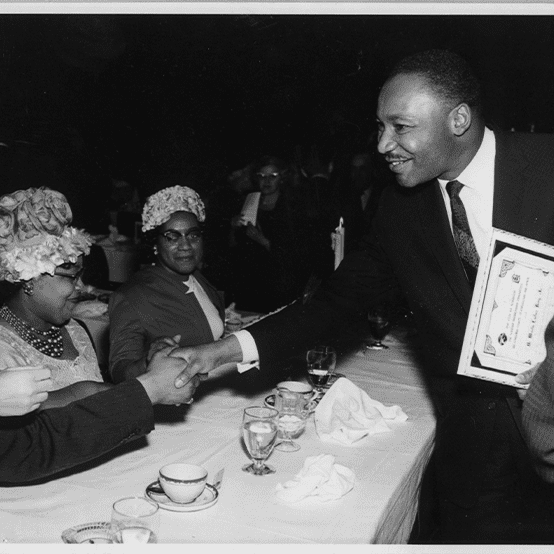

The Movement for Civil Rights

With the relaxation of employment barriers due to the war, African Canadians began a more concerted struggle for civil rights. The attitude had become, “if they can hire us in wartime, they can hire us anytime!”

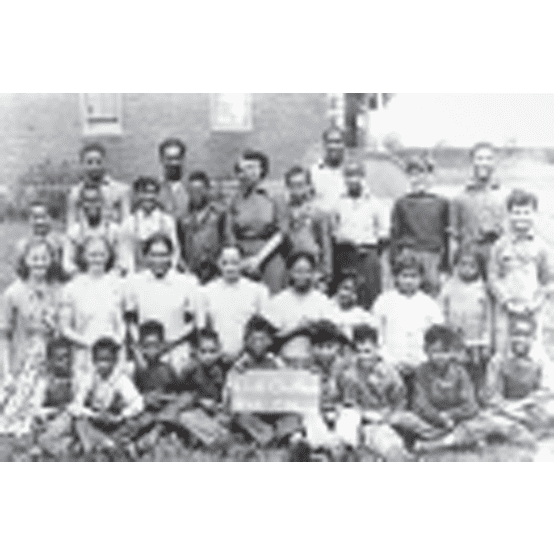

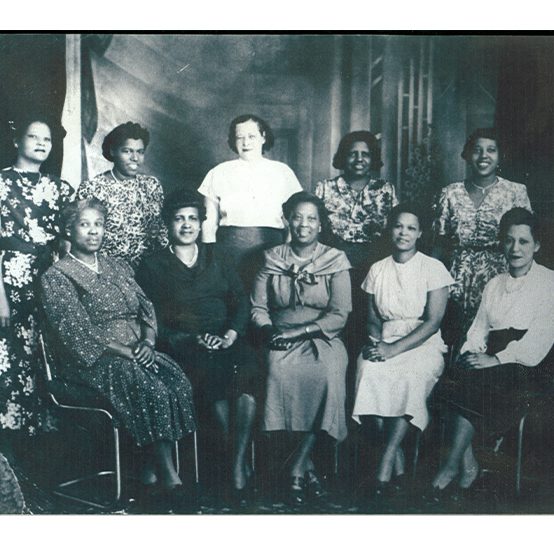

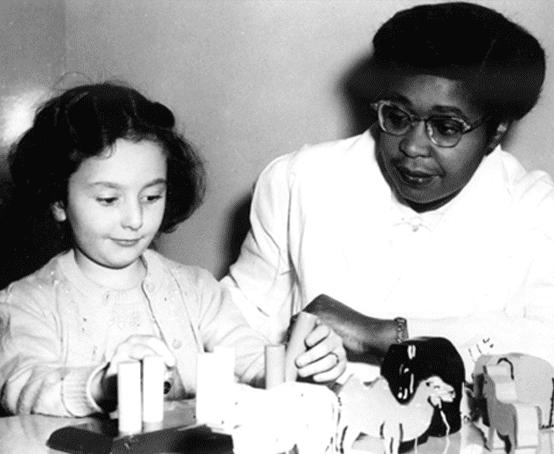

As a result of the pressure put on the provincial Ministry of Health and nursing schools by such groups as the Hour-A-Day Study Club of Windsor and the Toronto Negro Veterans Association, Black women were finally admitted for training and gradually employed in hospitals across Ontario by the late 1940s-early 1950s.

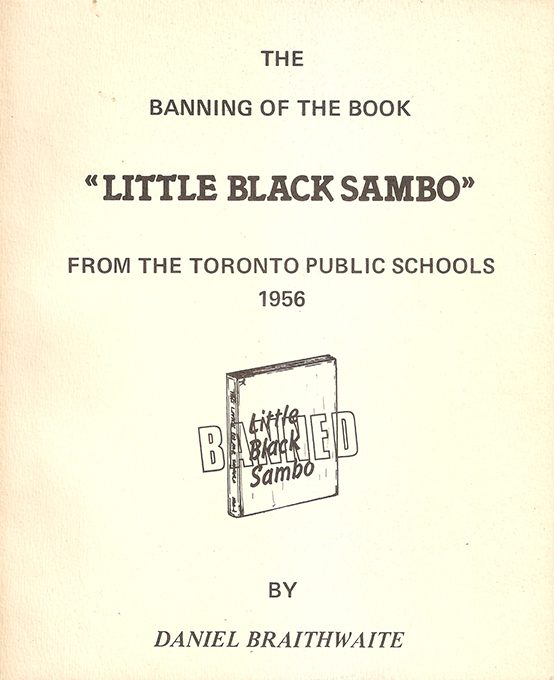

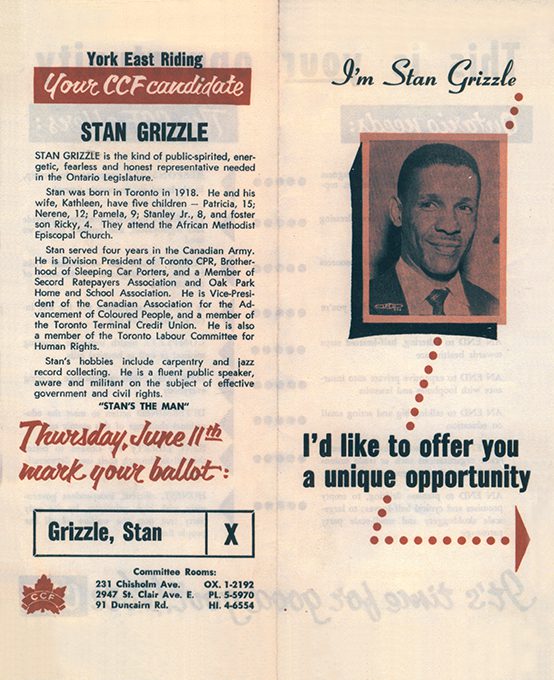

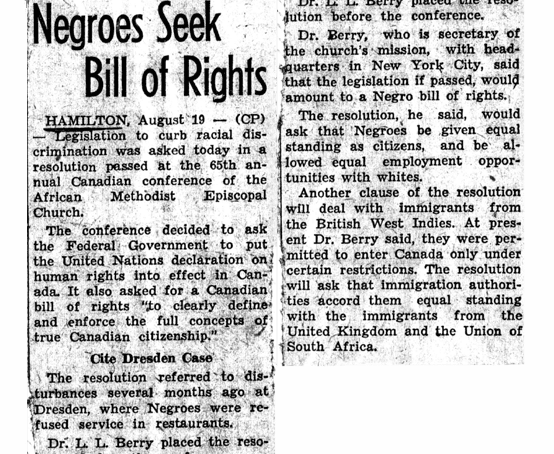

In the days before the street protests of the 1960s, African Canadians wrote letters, held meetings, sent delegations to Queen’s Park and Ottawa and staged sit-ins to protest their treatment. They aligned with progressive labour, religious and civil liberties groups.

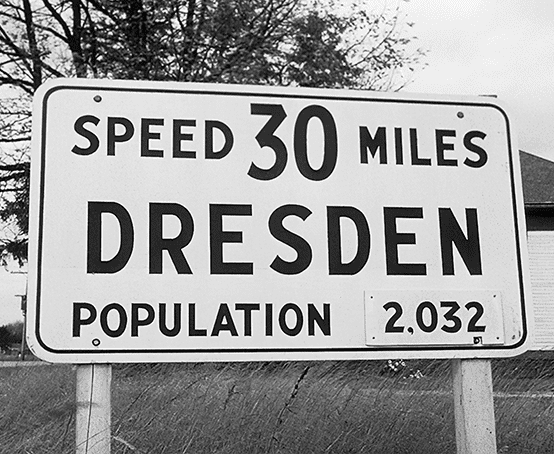

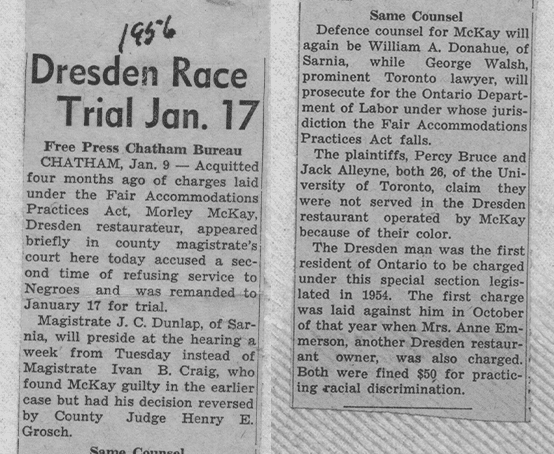

As a result of these actions, the Fair Employment Practices Act (1951) outlawed discrimination in employment and the Fair Accommodation Practices Act (1954) made discrimination in public accommodations illegal. When companies flouted the law, Black people directly tested their right to eat in restaurants, sit in movie theatres, skate at local rinks or rent the housing of their choice. Some companies were prosecuted and fined as a result. They started to get the message.

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/hamcivmus/public_html/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/hamcivmus/public_html/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

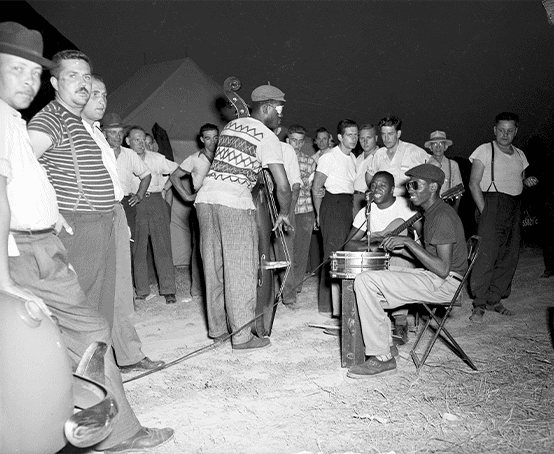

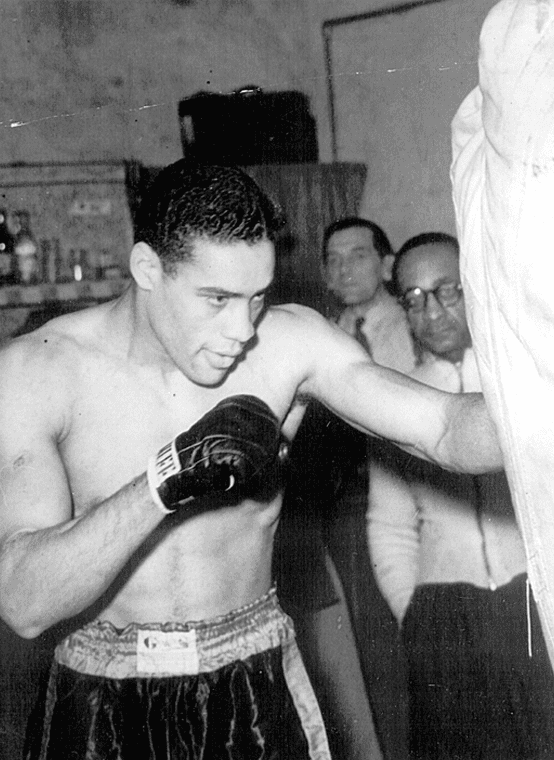

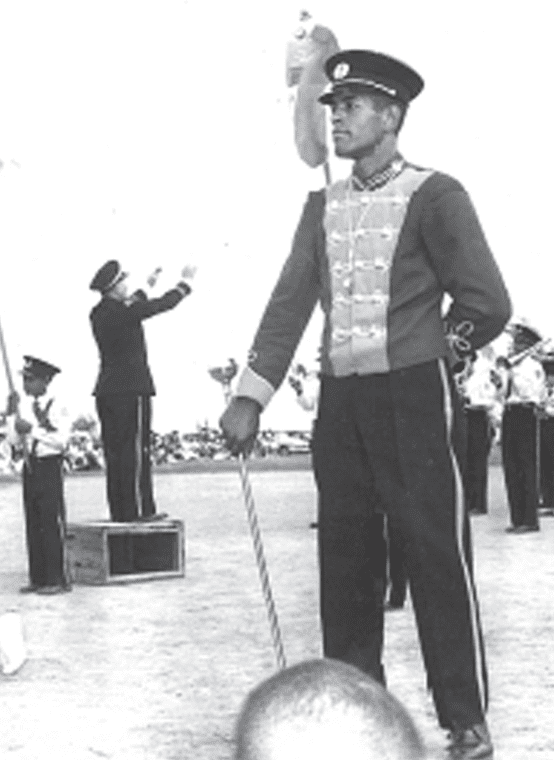

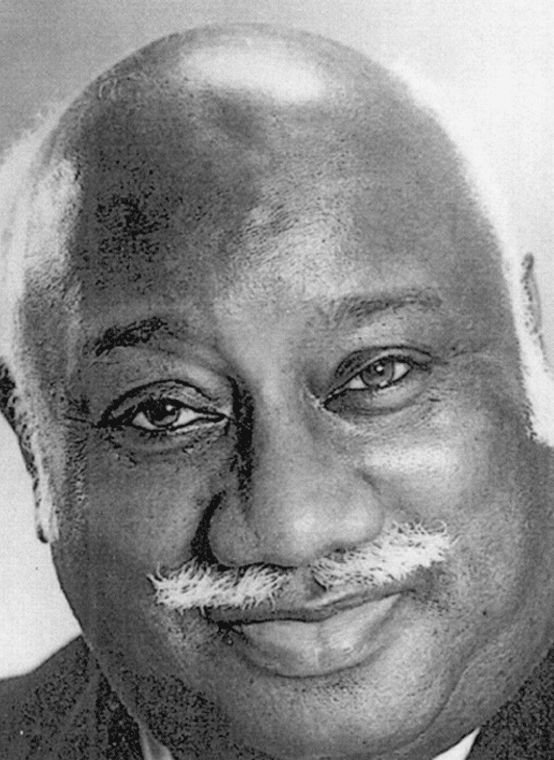

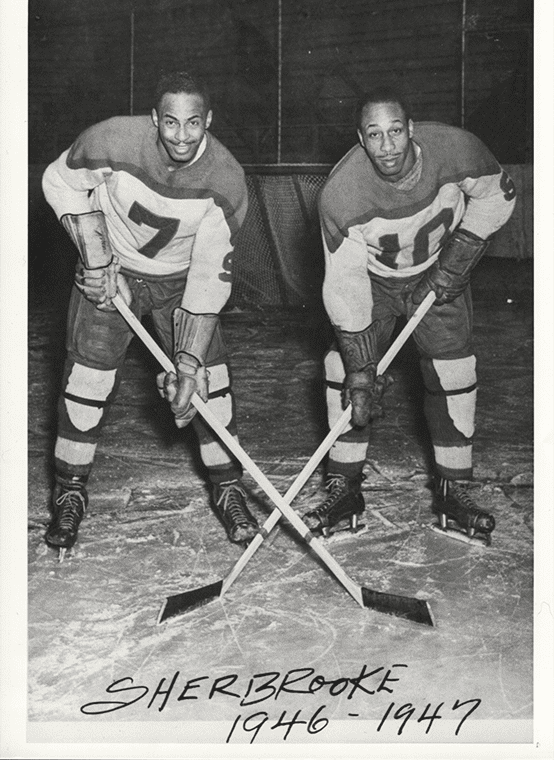

Breaking Loose

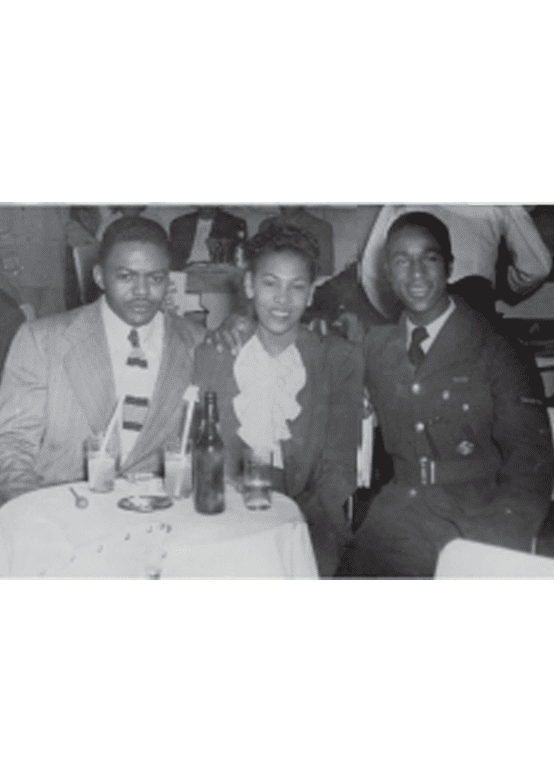

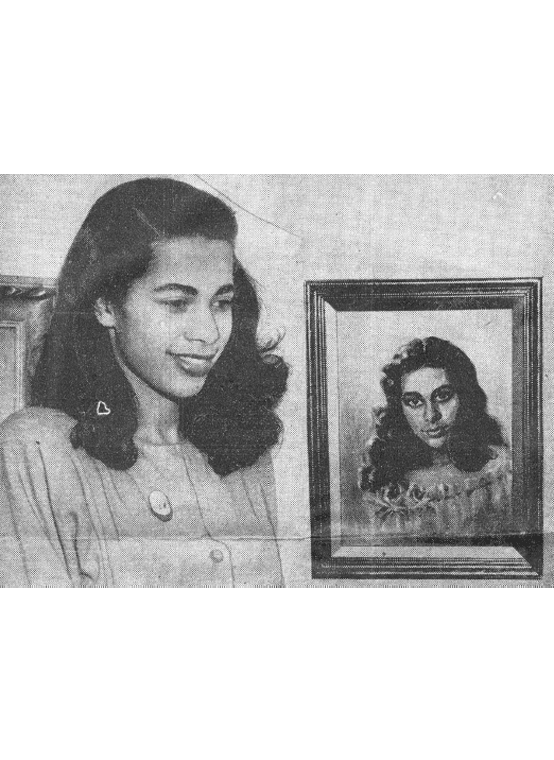

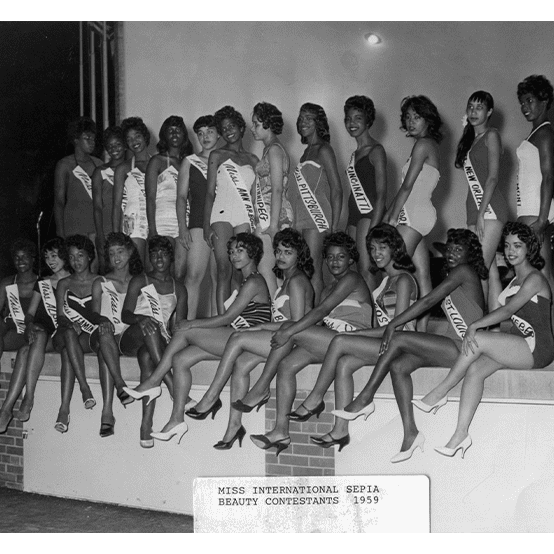

Just as the lindy hop and jitterbug broke loose of traditional dance forms, so too, African Canadians began to break loose of the racist restrictions that had kept them down. Community and cultural activities continued to play an important role in people’s lives.

As always, the community would produce those whose excellence and achievement could not be denied. However, many would still make the trek south to the United States. By contrast, the Canadian government – under pressure from the Black community to ease immigration restrictions – moved to admit Caribbean nurses and other professionals in the 1950s under the “exceptional merit” clause of the Immigration Act.

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/hamcivmus/public_html/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/hamcivmus/public_html/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2