Continuing the Fight: 1960s – 2000

A Changing World

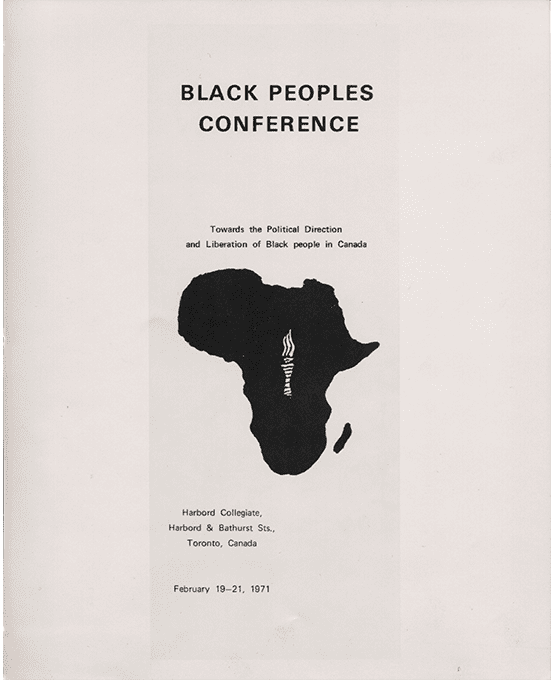

The nationalist and independence movements which took place in the 1950s and 1960s in Africa and the Caribbean had huge repercussions in the United States and Canada.

The latter governments realized that if they were going to have relations with these new Black nations, they had better clean up their own back yards. However, although Canada had its own fight for civil rights, it had been a relatively quiet affair, compared to that which took place in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s. In fact, the American civil rights movement had significant reverberations around the world, which in turn, impacted on movements for equal rights everywhere.

After decades of lobbying and criticism, the Canadian government finally addressed the problem of its racist immigration policies with the 1962 and 1967 Immigration Acts, which allowed unsponsored Caribbean immigrants to enter Canada for the first time, based on their skills and education. The families of prospective immigrants could now sponsor their relatives as well. As a result, between 1967 and 1996, over 300,000 from the Caribbean immigrated to Canada. At least another several thousand have emigrated from the continent of Africa each year since 1966.

Breaking New Ground

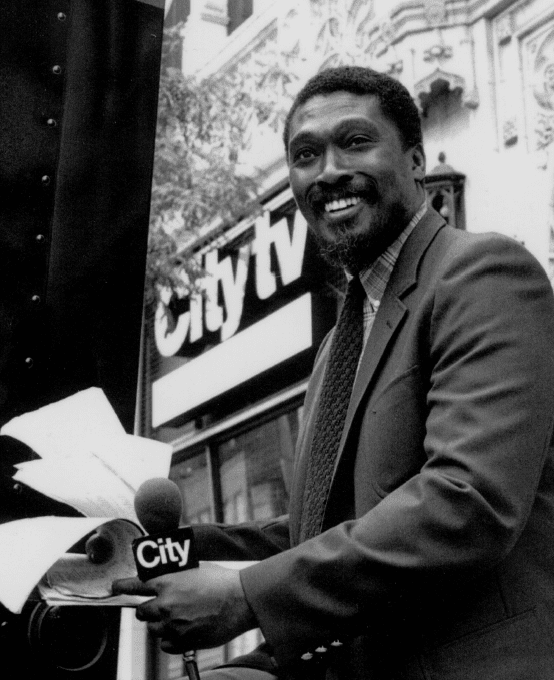

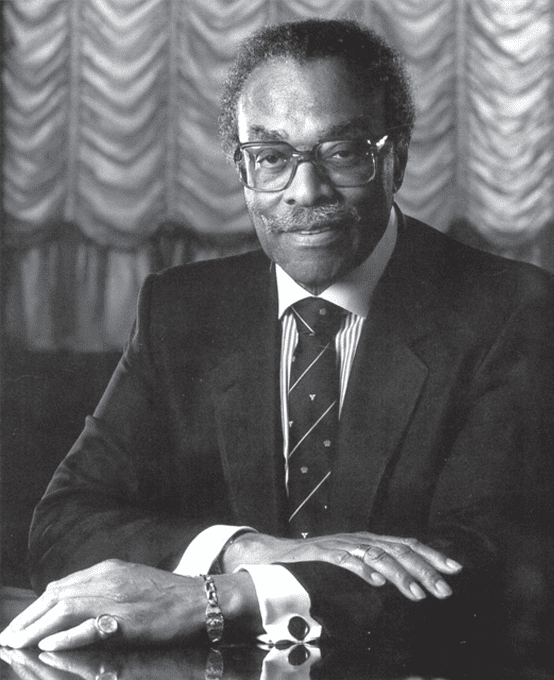

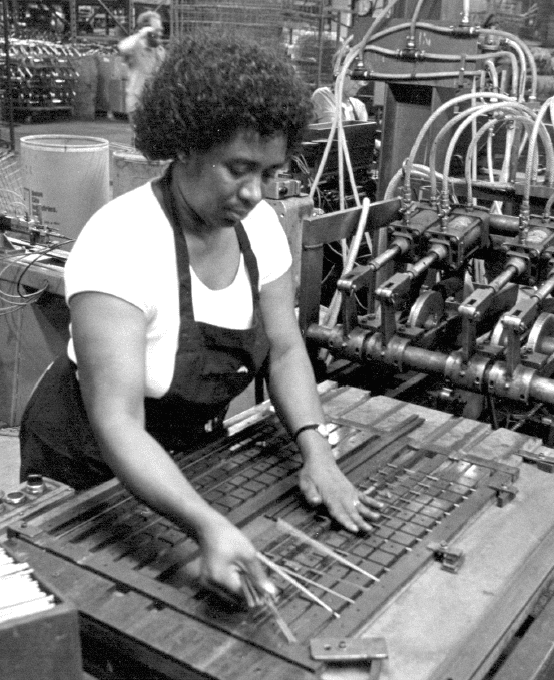

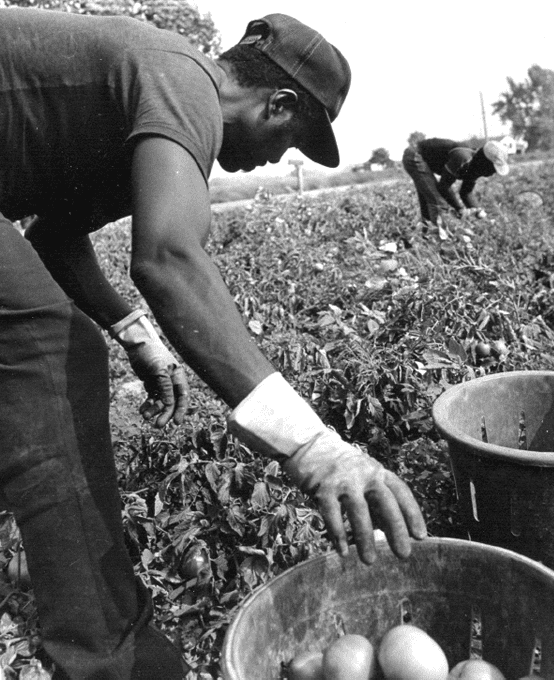

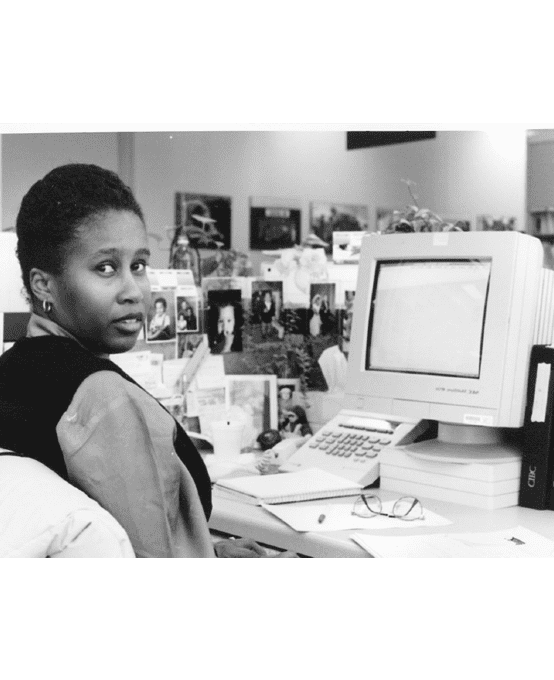

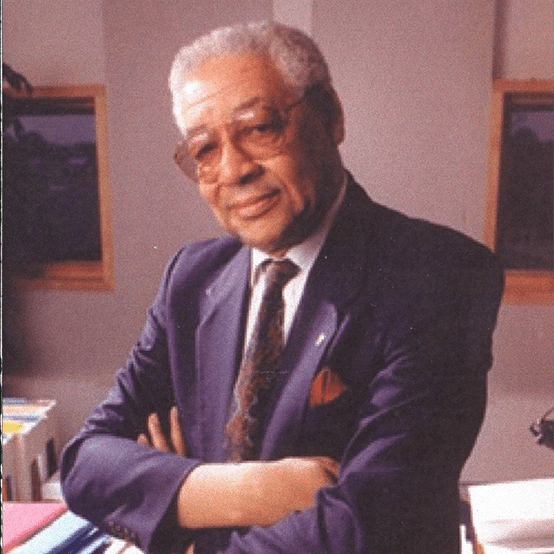

Ultimately, the fight for freedom and justice here at home and abroad began to bear fruit. Whether they were new immigrants or had been here for generations, African Canadians began to move into the mainstream of Canadian industry and the job market.

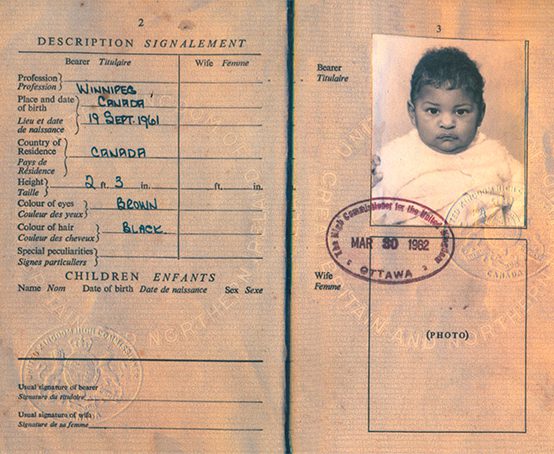

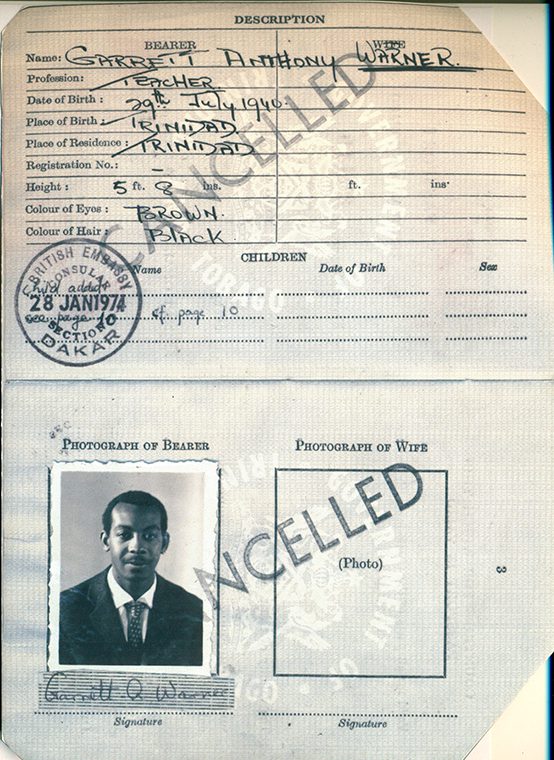

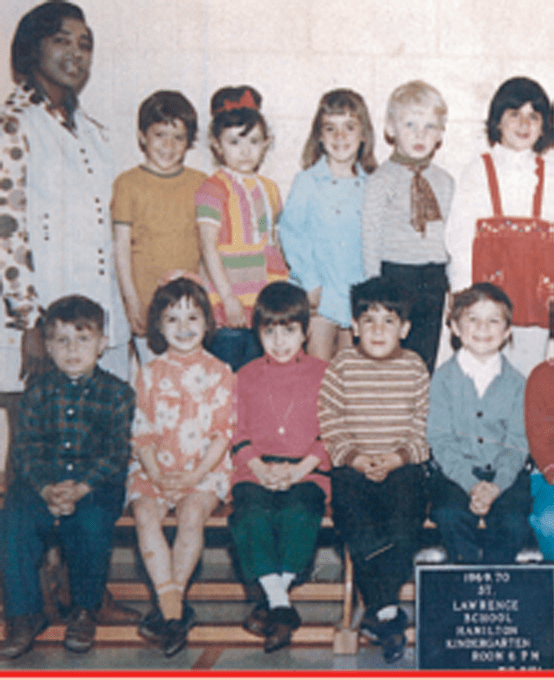

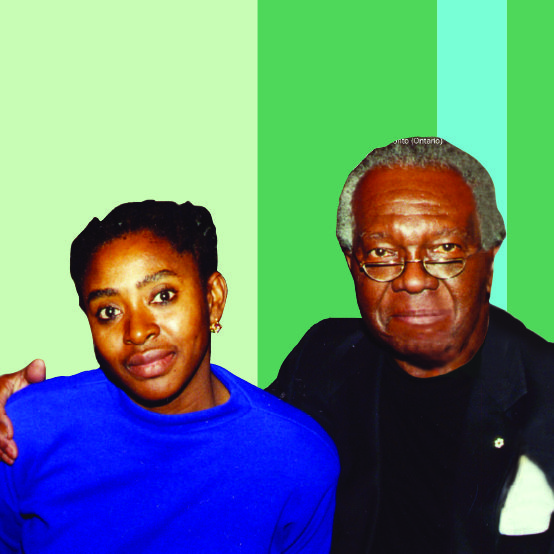

Contrary to the conventional wisdom of a flow of development resources from the North to the South, teachers from the Caribbean – primarily Trinidad – were recruited to fill a teacher shortage in Hamilton in the mid- to late-sixties. This South-North flow of human resources from Africa and the Caribbean to Canada has been felt across the province in a wide variety of fields. The passports of Roger Ferreira and Gary Warner (below) are representative of the thousands of people of African descent who came during this period and forged successful lives.

Continuing the Fight for Equity

|

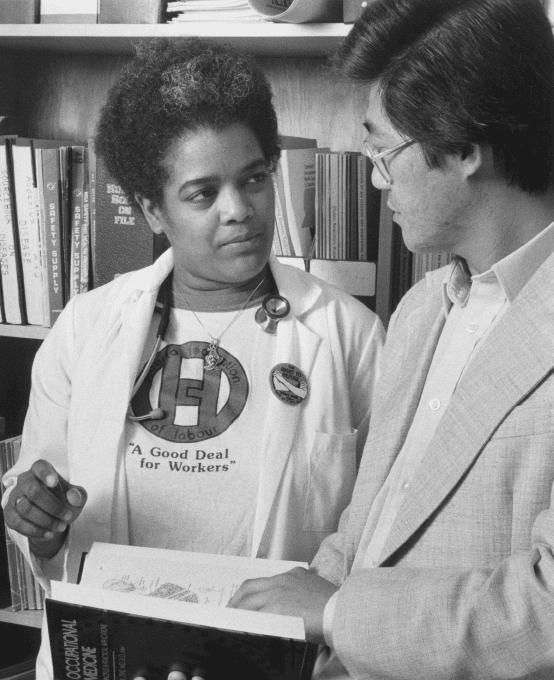

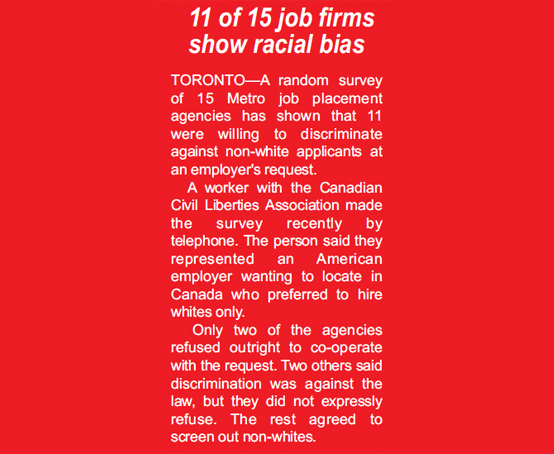

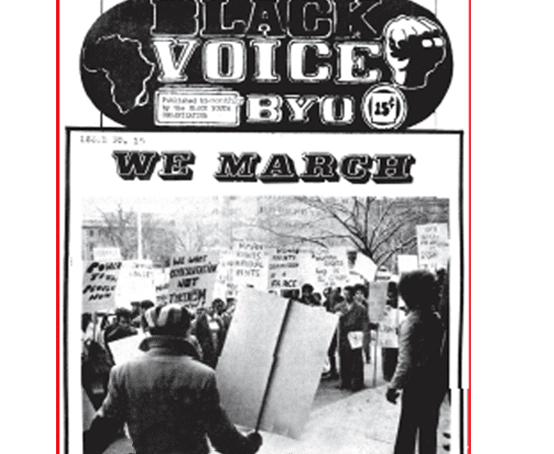

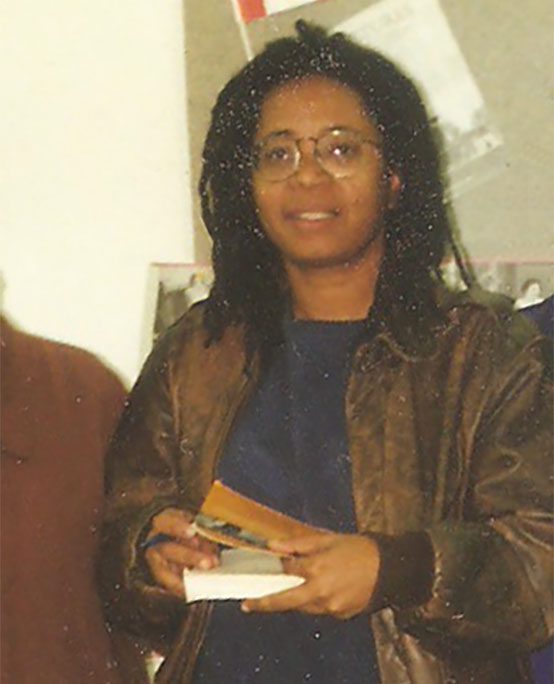

African Canadians have been at the forefront of the struggle for employment equity, reform in the education system and in policing, and in the overall fight for justice in society. They have pushed for greater representation in unions and formed human rights committees to address problems of racism in the workplace.

Black Community Today

The Black community of the 21st century is as diverse and multicultural as Canada itself.

Kwanzaa, the cultural holiday conceived and developed by Dr. Maulana Ron Karenga in 1966 is traditionally celebrated from December 26 through January 1, with each day focused on Nguzo Saba, or the seven principles.

Derived from the Swahili phrase "matunda ya kwanza" which means "first fruits," Kwanzaa is rooted in the first harvest celebrations practiced in various cultures in Africa and it seeks to enforce a connectedness to African cultural identity and for families and communities to come together and reflect upon the Nguzo Saba, or the seven principles, that have sustained Africans peoples. Zwanzaa is practiced by African Americans and African Canadians of all religious faiths and backgrounds.

Primary Symbols of Kwanzaa:

The straw mat, or Mkeka (M-Kay-cah), on which all the other items are placed is a traditional item and therefore symbolizes tradition as the foundation on which all else rests.

The candle-holder, or Kinara (Kee-nah-rah), holds seven candles and represents the original stalk from which we all sprang. It is said that the First-Born is like a stalk of corn which produces corn, which in turn becomes stalk, which reproduces in the same manner so that there is no ending to the people.

The seven candles, Mshumaa (Mee-shoo-maah), represent the Seven Principles (Nguzo Saba) on which the First-Born set up the society in order that African people would get the maximum from it. They are Umoja (Unity); Kujichagulia (Self-Determination); Ujima (Collective Work and Responsibility); Ujamaa (Cooperative Economics); Nia (Purpose); Kuumba (Creativity), and Imani (Faith).

The ear of corn, Muhindi (Moo-heen-dee), represents the product (the children) of the stalk (the father of the house). It signifies the ability or potential of the offspring, themselves, to become stalks (parents), and thus produce their own offspring -- a process which goes on indefinitely, and ensures the immortality of the Nation.

The Unity Cup, or Kikombe cha Umoja (Kee-coam-bay chah-oo-moe-jah), symbolizes the first principle of Kwanzaa. It is used to pour the libation for the ancestors, and each member of the immediate family or extended family drinks from it in a gesture of honour, praise, collective work and commitment to continue the struggle begun by the ancestors.

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/hamcivmus/public_html/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/hamcivmus/public_html/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

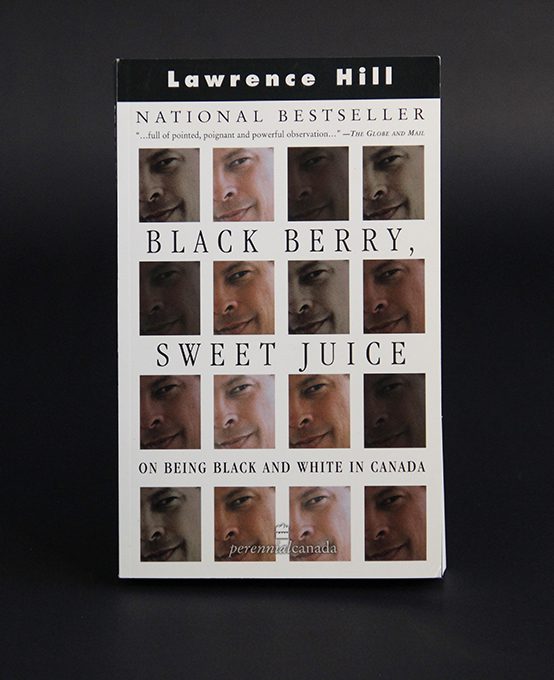

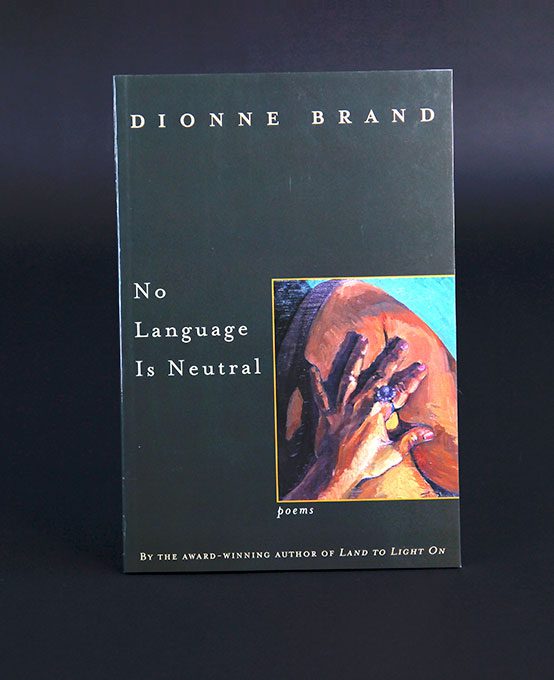

Language is not Neutral

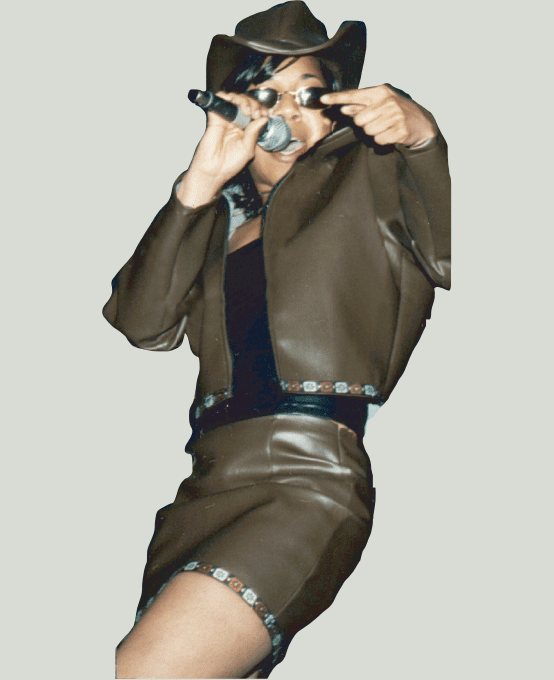

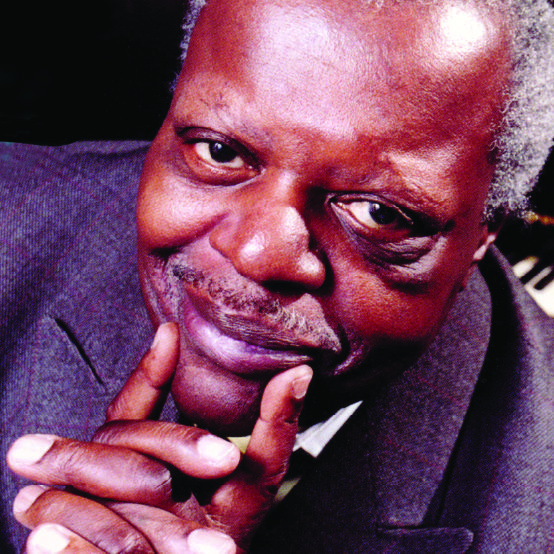

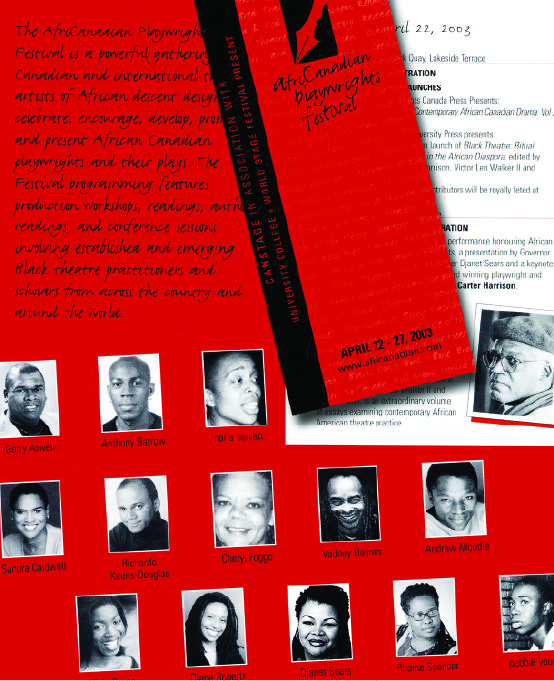

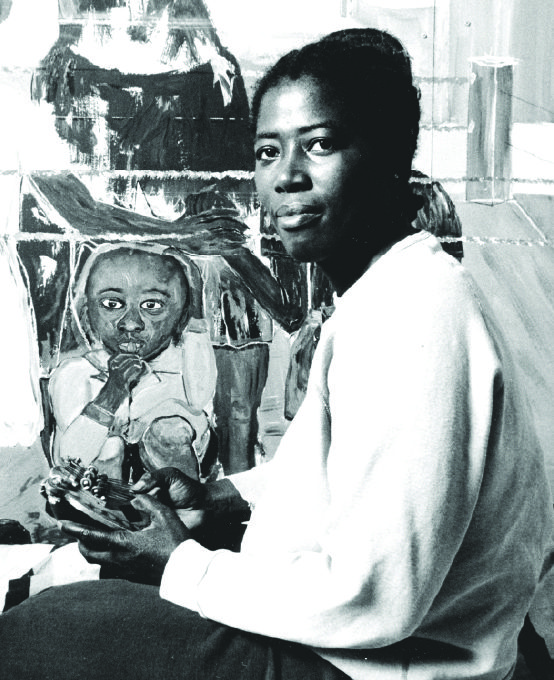

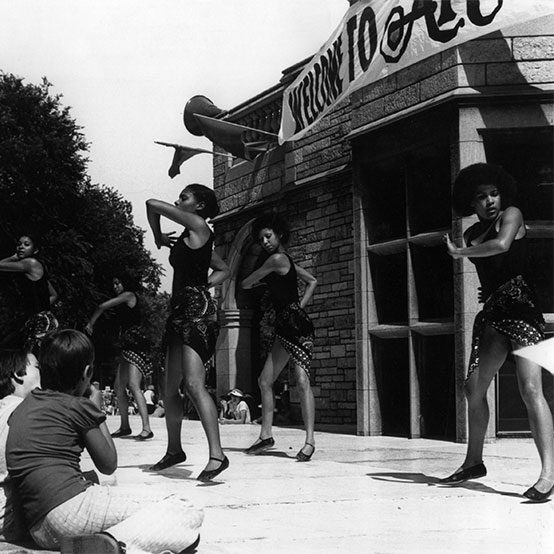

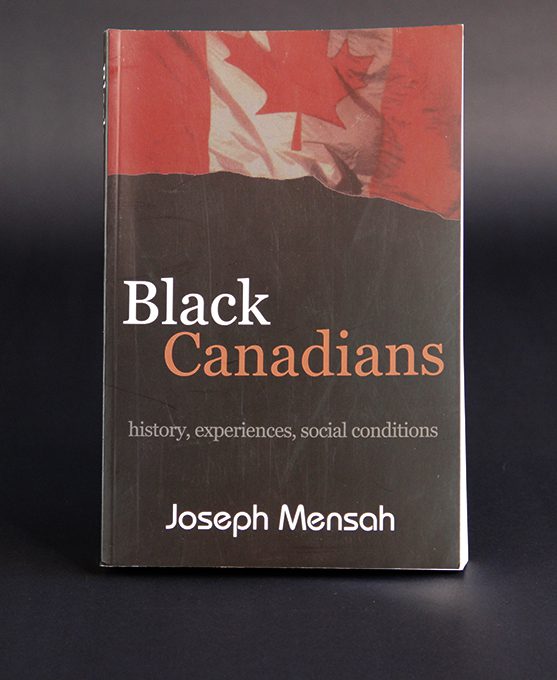

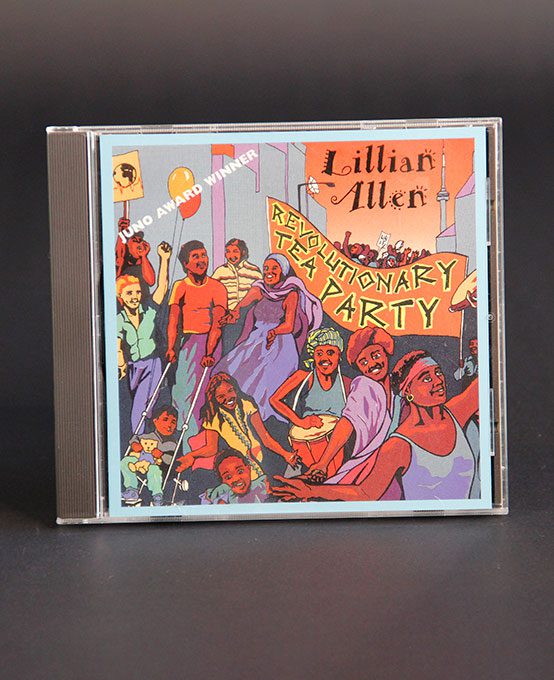

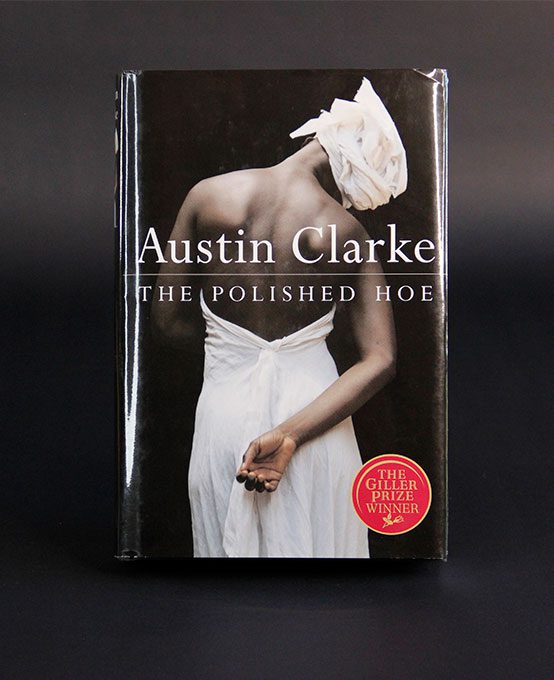

Coming from a wide mix of cultures, languages and nationalities, there is no one African Canadian national identity. Rather, the African Canadian identity, as reflected in its music, literature, art and dance, may be defined by its heterogeneity.

|

Despite their diversity, African Canadians of all stripes have been on a four-hundred-year quest for racial justice and equality. African Canadian cultural expression has symbolized that quest, and it has done so, whether consciously or unconsciously, by tapping into the wellspring of the African creative genius. |

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/hamcivmus/public_html/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/hamcivmus/public_html/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2